Sarah Clarkson is a writer who yearns to bring beauty, imagination, and great books to women around the world. Her blog is a source of contemplation and comfort, a place where readers can find spiritual courage and beauty for the road. Sarah is passionate about the power of reading to strengthen faith and form all sorts of goodness in the minds and souls of readers. She’s spent a decade writing and teaching on the power of stories to form children, but in Book Girl, her latest book, she writes about the profound grace that reading has been to her as a woman, a gift she cannot wait to share with women around the world. It’s a grace to welcome Sarah to the farm’s front porch today…

I sat in the rainy half-light of my tiny English living room, in the blank silence of the loss of my first child, a “little bean” I would never meet.

The world had gone so quiet.

My heart was so, so cold.

I found I could not command my feelings, either of sorrow or of hope.

Grief felt like the suspension of normal life—as if my entire being had been tossed up in the air and I was waiting to see what would crash to the ground and what was still safe.

The old things I loved—cooking, walking, writing—there was no help or joy in those for now.

I simply sat.

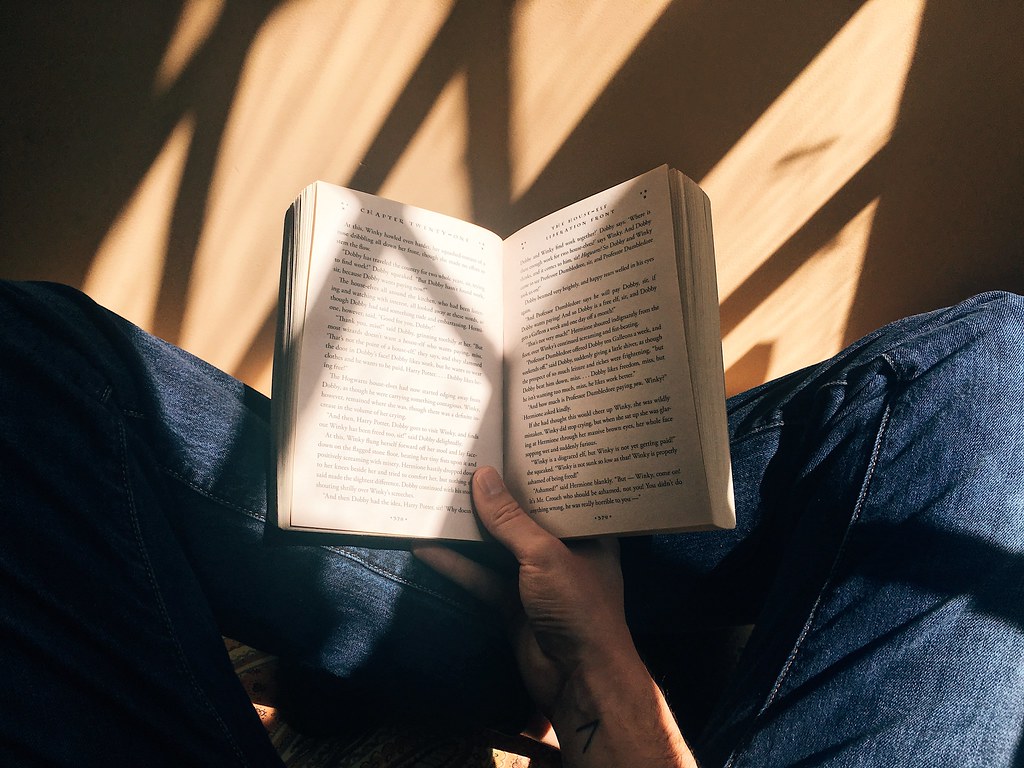

But reading was so deeply part of my habits that I found myself skimming a book brought by a friend before I really thought about what I was doing.

In that gray light I read about Julian of Norwich’s vision of something that looked “small as a hazelnut” but was actually the whole world, cradled in the palm of God’s hand, and her knowledge that “God made it. . . . God loves it. . . . God preserves it.”

I remembered that my baby was about the size of a hazelnut when he died.

I read on and found Julian’s luminous affirmation, chanted down through the war-torn ages, that because of the love of God “all shall be well, all shall be well, all manner of things shall be well.”

And I began to weep as my mind filled with the image of my own lost babe, held like the hazelnut of the world in the palm of God’s hand—not lost, but found, and waiting for me.

And in that moment I lived afresh the knowledge that a woman who reads has learned how to hope.

She understands that the grief of the present, small sorrow or searing pain that it may be, is not the final word.

“Love,” as Chris Rice croons in his ballad, “has the final move,” and the best stories teach a woman who reads how to frame her sorrow within the larger tale of both human endurance and divine redemption.

A good story, a piece of true theology, a radiant poem help us to look beyond the darkness of the present toward what Tolkien called “joy, joy beyond the walls of the world,” the light that endures beyond all pain and one day will invade our broken world to “wipe every tear from [our] eyes” (Revelation 21:4).

But a reading woman is also a realist; she lives in this broken place, and she grapples with the daily stuff of life in a fallen world.

Broken bodies, shattered relationships, a world in which wars and flat tires and miscarriages are daily realities—this is her story, and the great works of fiction and theology show her what redemption looks like in ordinary time.

I find it ironic that the reading of novels is sometimes criticized as an escapist activity, because some of the novels I love best are the ones that have taught me how to accept and survive the most grievous facts of my life.

It was Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country that first made me honest enough to admit the way personal pain made me doubt God’s goodness or the way grief made ordinary life feel pointless.

But it was that same book that showed me the possibility of a creative, stubborn faith that could endure even in total tragedy. Set in South Africa, in the era of apartheid, with two fathers grieving two sons, Paton’s story confronted me with this conversation:

“This world is full of trouble, umfundisi. Who knows it better? Yet you believe? Kumalo looked at him under the light of the lamp. I believe, he said, but I have learned that it is a secret. Pain and suffering, they are a secret. Kindness and love, they are a secret.

But I have learned that kindness and love can pay for pain and suffering. There is my wife, and you, my friend, and these people who welcomed me, and the child who is so eager to be with us here in Ndotsheni—so in my suffering I can believe.”

I needed those words…

Those words were the first in a series of novels that helped me to understand and see in character and plot that redemption isn’t something zapped down upon us but rather is rooted in the “deeper magic” (in Aslan’s terms) of God with us in the broken place, bearing our sorrow and turning death backward.

In the vision of Sam Gamgee, exhausted and alone in the deserts of Mordor, I learned that hope isn’t found in the absence of suffering but in glimpses of “light and high beauty” that help us to believe that “the darkness is a small and passing thing.”

Through the works of George Eliot and her tale of an abused and desperate wife who discovers God’s love through a preacher’s compassionate words, I learned that my small sorrows don’t leave me unable to help in “the blessed work of helping the world forward,” if only I will choose to act, to hope, to work.

Her words that “the real heroes of God’s making” come into their action “by long wrestling their own sins and their own sorrows” was a rallying cry to me, a challenge to rise from discouragement and learn to love, work, and hope again.

In your own journey, I’m sure you have discovered ‘comfort books’, those whose words have spoken light and hope to you as you sojourned in the shadowlands.

Whatever they are, I hope that they have taught you, like me, that we have the power to choose a gentle and holy defiance.

I can resist despair by choosing instead tiny, daily acts of creativity, kindness, beauty, and prayer, acts rooted in “the greater love that holds and cherishes all the world,”

and makes our lives a story whose ending is anchored in hope.

Sarah Clarkson is a writer fascinated by the way that beauty, imagination, and great books inform and inspire the life of faith. Through her blog, books, and current studies as a student of theology at Wycliffe Hall in Oxford, she explores the spiritual significance of story, the intersection of theology and imagination, and the capacity of beauty to give us hope. Her previous ‘books on books’ (Read for the Heart and Caught Up in a Story) explore the power of reading to profoundly shape a child’s heart and mind for good, while The Lifegiving Home, the book she wrote with her mom (Sally Clarkson) considers the powerful gift of home and the belonging and hope it brings.

In her newest release, Book Girl: A Journey Through the Treasures and Transforming Power of a Reading Life, Sarah explores the gift of the reading life and its power to shape and grace every season of a woman’s experience. Through personal essays, themed and unique book lists, and stories exploring her own journey as a reader, Sarah invites women – long time book girls and those new to the reading life – to discover books as companions whose wisdom and beauty offer hope, comfort, and joy in every phase of life’s journey.

[ Our humble thanks to Tyndale for their partnership in today’s devotion ]