Today’s blog post is special. Many of you know that I’m married to a farmer, and that we live on the land. The Lord so often speaks to me through everyday parables that are unfolding around me. Daniel Grothe has just written The Power of Place, which is a call to fall back in love with the place in which we are planted. Daniel is a pastor in Colorado Springs, and he lives on a ranch just outside of town with his family and a whole bunch of animals. There’s so much in this message that we need to hear in our age of hypermobility. It’s a grace to welcome Daniel to the farm’s front porch today…

I come from a long line of agrarians, salt-of-the-earth farmers and ranchers, and lovers of the land who lived in small towns across Washington and northern Idaho.

The patches of skin that for decades were exposed to the scorching sun and howling wind—the forearms and hands, the ears, the back of the neck—were permanently transfigured, a collage of various colorations arranged on one body. There’s a reason they call it a farmer’s tan.

As a family, we treasure the fifty years’ worth of daily journal entries that were scribed by my great-great-grandmother Lula Wilson and her daughter-in-law, my great-grandmother, Lucille Kemp Wilson. Lula and Lucille were the most recent matriarchs in my line.

These journals give a glimpse into the life of a family living on a rural farm. You can thumb your way through Lula’s journal and see the textures of a rural community just as the darkness of the Great Depression was descending across the land. Here are a few of those entries from 1930:

June 30: 16 loads of hay hauled in today. Burl [her son], Mick, Elmer and a stranger worked. Lucille and all the children are here. White sow bred today.

September 6: Little yellow calf born.

September 22: Canned 6 quarts of beans, 6 quarts of corn. Fried 2 chickens for dinner. Finished digging potatoes, 10 sacks.

December 25: A beautiful morn—Burl called to wish all a merry Christmas—a wonderful Xmas, grand dinner, the table looked beautiful, the dinner was swell.

Lula was an amputee, having lost a leg to diabetes. Can you imagine the quality of the health care along the back-country roads of small-town Washington?

Health care was virtually nonexistent, but somehow Lula made it. Their existence was spare and spartan, and they prayed that famous line from the Lord’s prayer literally: “Give us this day our daily bread” (Matthew 6:11 ESV).

On August 17, 1901, Lula had a son who would much later become my great-grandfather. His name was George Burl Wilson. Young George grew tall, and at least to his father’s eyes, his gangly, narrow legs looked like thin boards, like skinny slats of wood. So he was nicknamed Slats.

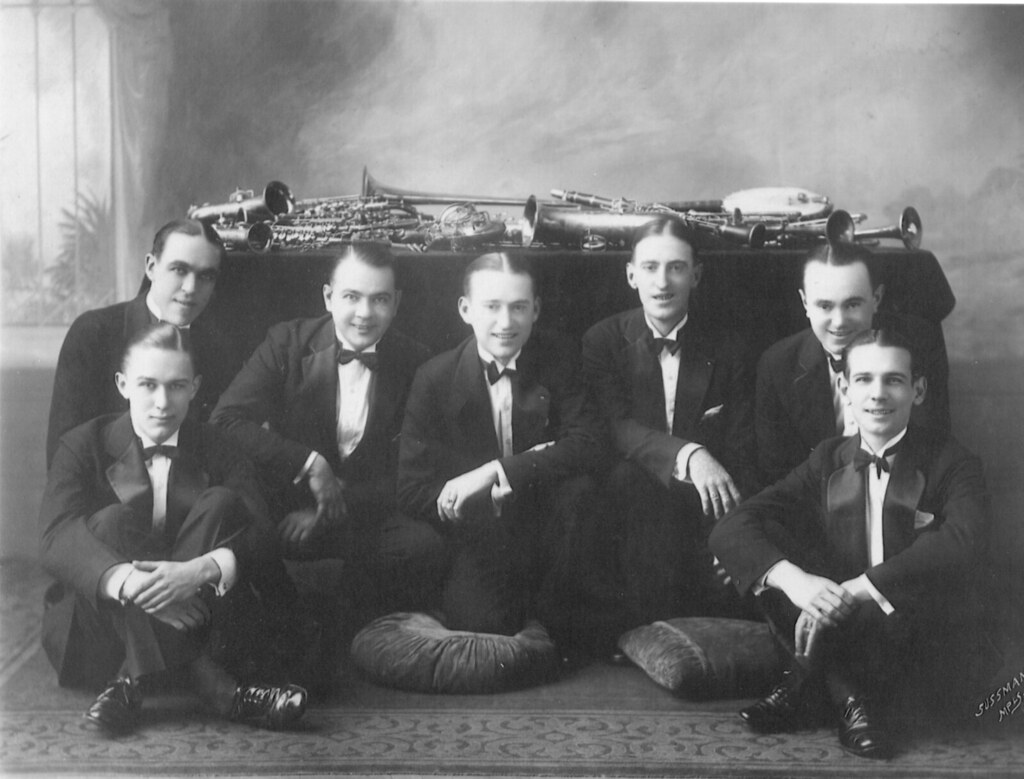

But my agrarian ancestors were also fantastic musicians. The banjo was their instrument of choice, the rhythmic and melodic backbone of the family band, and whenever they would gather in the living room or around a bonfire, everyone sang their part—soprano, alto, tenor, bass. Great-grandpa Slats demonstrated a knack for the banjo and quickly became a rising star in the region. In his early twenties he started playing professionally, joining the Mann Brothers Orchestra.

This was America’s era of vaudevillian music, of the dance halls and concert saloons, and the seven young men toured the country, playing the Pantages Theater Circuit, a robust franchise with eighty-four theaters across the country.

The Mann Brothers Orchestra played a stretch of weekly shows in Lewiston, Idaho, that had more than 5,000 people dancing on the lawn every Friday night. These guys were small-town boys from Idaho and Washington, and they were taking the nation by storm. Everywhere they played they wore expensive tailored tuxedos, quite a departure from the bib overalls and boots they grew up wearing on their family farms.

But one night in Kansas City, and out of nowhere, my great-grandpa Slats walked off the stage and quit the band. An invisible fault line had shifted in the economy, and the nation was in tremors. Deep fissures were splitting open. They were now seeing the bottom of the Great Depression.

“By wearing his tuxedo to work on the farm, I think Slats was onto something. The land is a place to hallow the Name, a beautiful sacrament to be received and enjoyed.”

Several of Slats’s musician friends were having to stand in soup lines from town to town to find a meal. So he quit, telling his bandmates he’d never be seen standing in a soup line, waiting for a meal. To casual observers, this may sound like pride. But knowing my family heritage as I do, I actually think it was the response of a man who felt duty bound to serve his nation in a moment of national crisis.

Instead of asking for bread, he’d go home and grow wheat that would help feed his country. He grew up on the land and knew how to nurture it into a luxuriant yield. He knew that the nation would need farmers to carry her through these years, so he quit the band, got on the first train heading west from Kansas City, and went back home.

During Slats’s first year back on the farm, he regularly wore his expensive tuxedo as he plowed the fields.

Can you imagine a man riding behind his draft horses plowing a field in a tuxedo? The Pulitzer Prize–winning writer Marilynne Robinson remembered her grandfather working his garden in his best suits too.

“They were just too nice to throw away,” said Great-grandpa Slats.

Slats may have thought he was just being frugal, but I think there is a deeper meaning for those who care to pay attention. We wear tuxedos when we know we’re involved with the sacred. We wear tuxedos when we want to hallow a moment. We wear tuxedos as a threaded signal that we recognize we’ve been tangled up in the eternal.

By wearing his tuxedo to work on the farm, I think Slats was onto something. The land is a place to hallow the Name, a beautiful sacrament to be received and enjoyed.

“The place you are standing is holy as well.”

On his first day back on the farm, I imagine my great-grandpa Slats getting up early and getting ready for the day. He was back to his place of birth, back to the backbreaking work on the land.

There would be no adoring fans to cheer him. There would be no fancy lighting or boisterous introductions. There would be no elevated stage and no one dancing just below it. Just a man, his family land, and a tuxedo.

At the burning bush, Moses was told to take off his sandals, “for the place where you are standing is holy ground” (Exodus 3:5). On that first day, I can imagine Slats hearing something like: Put on your tuxedo. For the place where you are standing is holy ground.

And the place you are standing is holy as well. To the stay-at-home mom, remember that you’re standing on holy ground.

All you schoolteachers, you’re on holy ground.

From the janitor to the junior partner in the law firm, from preschoolers to presidents and prime ministers—and everywhere in between—

we’re all standing on holy ground.

Daniel Grothe is the associate senior pastor at New Life Church in Colorado Springs, Colorado, where he’s been for sixteen years. Daniel and his wife, Lisa, live on a hobby farm outside of town with their three children—Lillian, Wilson, and Wakley—and a thriving throng of happy animals.

In The Power of Place: Choosing Stability in a Rootless Age, Daniel helps us reclaim the ancient vow of stability. He teaches us that our feelings of restlessness open us up to our deepest longing for a lasting community, to our desire to be known, and to our need for a place to call home.

He calls us to reject the myth of Christian individuality and instead embrace the richness of commitment and community, arguing that we must stay in one place as long as we can, plant our lives, and let roots take hold. Because only then can we experience the deep fulfillment, friendship, and fruitfulness God created us for.

[ Our humble thanks to Thomas Nelson for their partnership in today’s devotion ]