One glance at the headlines will tell you that the world is a dangerous, confusing place. Forget the headlines—just look at your social media feed. From global tragedies to interpersonal conflict, it can feel like the only choice you have left is to hunker down and do your best to survive. But what if God wants more for you in this life than survival? Better yet, what if He has a plan to restore the goodness of the world? What if you’re part of that plan? Hannah Anderson invites you to embrace discernment as part of God’s larger work of redemption. By learning to see the world as He sees it—in all its brokenness and beauty—you’ll learn how to navigate it with hope and confidence. And when you learn to pursue whatever is true and lovely and pure and just, you’ll find yourself changed. So come, join in this journey to wisdom. Come, find the freedom of discernment. Come, discover all that’s good. It’s a grace to welcome Hannah to the farm’s front porch today…

When we started from the city’s main station, exiting into a maze of unfamiliar streets and traffic patterns, the sky was looming, dark clouds gathering themselves above us.

An hour later when we were still walking, lost, cold, and hungry, the clouds had become a steady drizzle, drip-dropping on our heads.

Despite being on a trip of a lifetime, all I wanted was to be at home.

Our family lives in the blue mountains of rural Virginia. My husband grew up here and we’re raising our children here, putting down roots, drinking from the richness of community and family and home.

But we know that healthy plants must grow upward and outward.

We know that we’ll have to challenge the anxiety that can so easily develop in small places.

We know we’ll have to show them that larger cities and foreign places and new things are nothing to fear.

So we scrimp and save and forego the immediate for the timeless.

But when you’re tired and homesick and miserable, wandering the streets of Paris, you start to wonder whether the broader world is so important after all.

Hannah Anderson

Hannah Anderson

We finally found a spot for lunch, and after a few minutes with a map, made our way into the Louvre, bypassing the main entrance for a less frequented one in the Place du Carrousel.

Out of the elements, we relaxed, meandering through hall upon hall of beauty and goodness. Eventually, we found ourselves surrounded by ancient statuary, studies of the human form stretching as far as the eye could see.

My children’s discomfort from walking in the rain suddenly dwarfed by the awkwardness they felt at seeing so much nakedness depicted so freely and so accurately.

Leaving them to gape, I wandered ahead to a figure of a woman kneeling.

Her back was toward me, the smoothness of the marble perfectly accentuating the curve of her spine, the fluid lines and skilled craftsmanship lending her body the appearance of softness. Instinctively, I moved toward her, but as I did, I noticed a small mound protruding from her back. It looked like a growth of some kind, entirely at odds with the rest of the statue. But then I caught my breath. I knew what it was.

It was a small, chubby hand.

It was the hand that once reached up to touch my face with wonder, curiosity, and unashamed ownership.

It was the hand that grabbed at my necklaces and played with my hair when I forgot to tie it back. The hand that slowly but surely gained control over its movements, first learning to grasp and then to pinch. The hand that eventually figured out how to hold a pencil, catch a ball, and play the piano. It was the hand that still reaches for me in unfamiliar places—the hand that had all morning clutched for the reassurance of my body in the rain and confusion.

A plaque identified the statue as Crouching Aphrodite: the goddess of love at her bath, and the hand belonged to her son Eros who, as children do, had interrupted her.

Over the millennia, Eros had broken off at the wrist and been lost.

But attached to the main part of the statue, the small, chubby hand survived. The disfigurement was startling, and in a way, grotesque, testament to how far the statue had come from what it once was.

But in another way, it testified to a deeper reality.

In Mere Christianity, C. S. Lewis reflects that he had once argued against the reality of God because the universe seemed cruel and unjust. “But how,” he wonders, “had I got this idea of just, unjust? A man does not call a line crooked unless he has some idea of a straight line. What was I comparing the universe with when I called it unjust?”

Standing in the Louvre on a rainy autumn afternoon, I could not see Crouching Aphroditeas she once was.

I could only see what was in front of me.

But for all that I could not see, I was learning to discern the goodness of the original.

Because how else do you know Eros exists except by a small, chubby hand that rests on his mother’s back?

How else do you know that things are not as they should be except by the pain and loss you experience when you encounter them?

For all that we can’t see clearly in this world, for all that is broken and gone missing, we do know that things are not as they should be. We know that we are not what we should be.

But in some strange way, this confirms goodness.

In some strange way, the struggle proves we were made for more.

Dutch theologian Henri Nouwen describes discernment as the ability to “‘see through’ the appearance of things to their deeper meaning and come to know the interworkings of God’s love and our unique place in the world.” It’s the ability to see the world as it should be and believe that God is powerful enough to restore it. To know that a good God sent His good Son to make us good once again.

******

We left the Louvre just as the skies broke into a downpour, a full-fledged lapluie torrentielle. Soaked and shivering, we flagged a taxi to take us to the attic apartment we’d rented in the Montmartre district.

On the way, the children dozed, lulled to sleep by the stress of the day, the warmth of the cab, and the slow pace of rush hour traffic. My husband put his arm around me, and I leaned into him, resting my head on his shoulder.

By the time we arrived and ascended the dozens of steps, the rain had ended, leaving behind a clear sky and setting sun. From a skylight in a timbered attic, I watched the lights of the city emerge one by one. The echo of the television drifted up from the apartment below where the children cuddled together under a thick blanket, watching cartoons.

To my left, I could see Notre Dame and to my right, the Eiffel Tower. Behind me, high on Butte Montmartre, sat the majestic edifice of Sacre-Couer Basilica, her travertine towers and magnificent domes illuminated against the quickly darkening sky.

In the chaos of the world, it’s tempting to believe that brokenness is ultimate.

And if it is, then the best thing we can do is find a safe place, gather our loved ones, and hunker down.

But what if the brokenness testifies to goodness?

What if we could learn to “see through” to the deeper meaning of things and discover the beauty and love of God?

“I would have despaired,” David sings, “unless I had believed that I would see the goodness of the Lord in the land of the living” (nasb).

But we do believe.

And we will see His goodness.

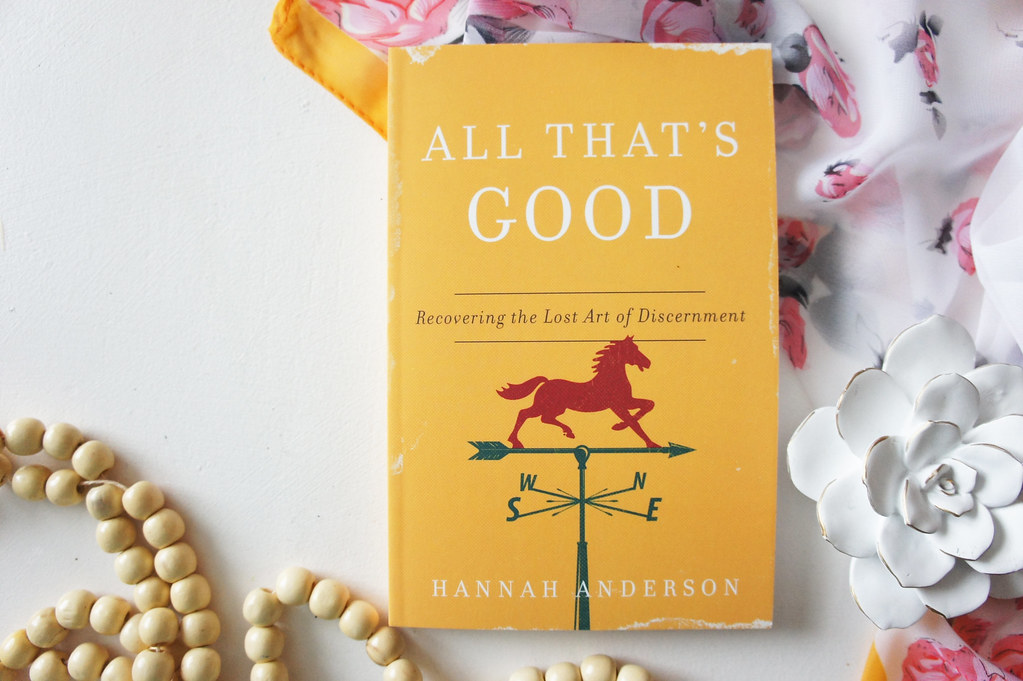

Hannah Anderson lives in the haunting Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. She spends her days working beside her husband in rural ministry, caring for their three children, and scratching out odd moments to write. In those in-between moments, she contributes to a variety of Christian publications and is the author of several books including Humble Roots: How Humility Grounds and Nourishes Your Soul and the newly released All That’s Good: Recovering the Lost Art of Discernment.

In this latest book, All That’s Good: Recovering the Lost Art of Discernment, Hannah shows readers how discernment and goodness dovetail one another as she explains how experiences, people, and objects have been a gateway to her personal understanding of the goodness of God: A long-anticipated vacation, the warmth of a fireplace, a family heirloom.

[ Our humble thanks to Moody Publishers for their partnership in today’s devotion ]