A journalist and mom of three, Whitney lived under the shadow of her mother’s cancer diagnosis for much of her childhood and into her adult years. But it wasn’t until cancer took her mother’s life twenty years later that Whitney began to understand: this valley of the shadow of death was always meant to teach us how to live. In this excerpt from her new book, she writes about how facing death changes our perspective on the bodies we inhabit for now. A humble grace to welcome Whitney to the farm’s front porch today…

Guest Post by Whitney Pipkin

I may not remember many of the ancestry facts Mom dredged up in her later years, but I remember her skin. It is a map in my mind telling the story of her life as it evolved over time.

Later, it was the first part of her body to bear the marks of cancer treatment. I remember one chemotherapy drug that took a particular toll on the flesh of her hands and feet.

This medicine somehow managed to spare the hair, leaving her blonde bob intact for a time, while pooling instead at the end of her extremities. There, it wreaked havoc on the quickly-dividing skin cells, turning her palms puffy, raw, and red. They peeled so badly that the lifelong banker joked about robbing a few financial institutions now that her fingerprints had nearly disappeared.

Our bodies often tell us stories we’d rather not hear.

This was especially true of my mom, who endured more than most bodies can handle during countless clinical trials (“a real guinea pig,” she’d say). It wasn’t until I read her cancer notebook after she died that I realized how constantly she played whac-a-mole with bodily symptoms, beating back one only to be waylaid by another.

What hope is there for those who endure like this, I wonder now, in bodies that once flourished but now falter and suffer?

Our bodies carry in them reminders that we will not live forever. This is as true of those who have been given a terminal diagnosis as it is of those who have not. The skin that dimples fresh and dewy around a toddler’s chubby knuckles eventually flattens and freckles. In old age, it grows thin and papery, like tissue paper that barely conceals the blue veins still pumping beneath the surface.

“In our bodies, then, we carry all the beautiful and terrible tensions of the gospel.“

The Bible, unlike the advertising industry, does not shy away from this reality. It compares our bodies to pop-up tents and to jars of clay—the reusable Tupperware equivalents of the ancient world. Scripture says we inhabit “bodies of death” that are weak and perishable. Yet, illogically, our bodies are also called “[temples] of the Holy Spirit” (1 Cor. 6:19) and “fearfully and wonderfully made,” knit together by a careful Creator in our mothers’ wombs (Ps. 139:14).

In our bodies, then, we carry all the beautiful and terrible tensions of the gospel. Remembering this gives us categories for the painful parts of being embodied—and lends us a greater vision for their redemption.

The first body was formed when God breathed life into dust, making humans the climax of a creation that He called “very good.” Then the fall ushered frustration, futility, and death into every aspect of that creation, including our bodies and the work they were made to do.

When our frames are fading and frail, this is the part of the story they tell: “For you are dust, and to dust you shall return.”

It’s a story that could end there. But it didn’t.

When the fullness of time had come, the story burst into living color. “The Word became flesh and dwelt among us” (John 1:14). The very God through whom all things were made robed Himself in frail humanity. The One who made us in God’s image, imago Dei, took on a nature like ours to become God with us, Immanuel.

“The very God through whom all things were made robed Himself in frail humanity. The One who made us in God’s image, imago Dei, took on a nature like ours to become God with us, Immanuel.“

Our God took on a body.

Jesus Christ grew from infancy to manhood in a temporary tent like yours and mine. He who said “If I were hungry, I would not tell you, for the world and its fullness are mine” (Ps. 50:12) submitted Himself to basic bodily needs for food, clothing, and rest. Being embodied allowed Jesus to be “tempted as we are, yet without sin” (Heb. 4:15). Living the perfect life, which only He could do, made His body the spotless sacrifice for the sins of us all.

In this way, Christ’s embodiment lights the way for the redemption of our own: You whose body has been broken by the sins of others, you who suffer from chronic illness, you who struggle to receive the wrinkles and the wear-and-tear, “fix [y]our eyes on Jesus, the author and perfector of our faith, who for the joy set before Him endured the cross, scorning its shame, and sat down at the right hand of the throne of God” (Heb. 12:2 BSB). ***

What ailment befalls you?

What would change if you could lift your eyes not to a God who stands far off but to a Savior who stooped to suffer?

“Just as we have borne the image of the man of dust,” 1 Corinthians 15 tells us, “we shall also bear the image of the man of heaven” (v. 49).

The Savior whose return we await “will transform our lowly body to be like his glorious body, by the power that enables him even to subject all things to himself” (Phil. 3:21).

Whitney K. Pipkin lives with her husband, three children and a dog named Honeybun in Northern Virginia, where they are longtime members of Grace Bible Church in Lorton. She works as a journalist.

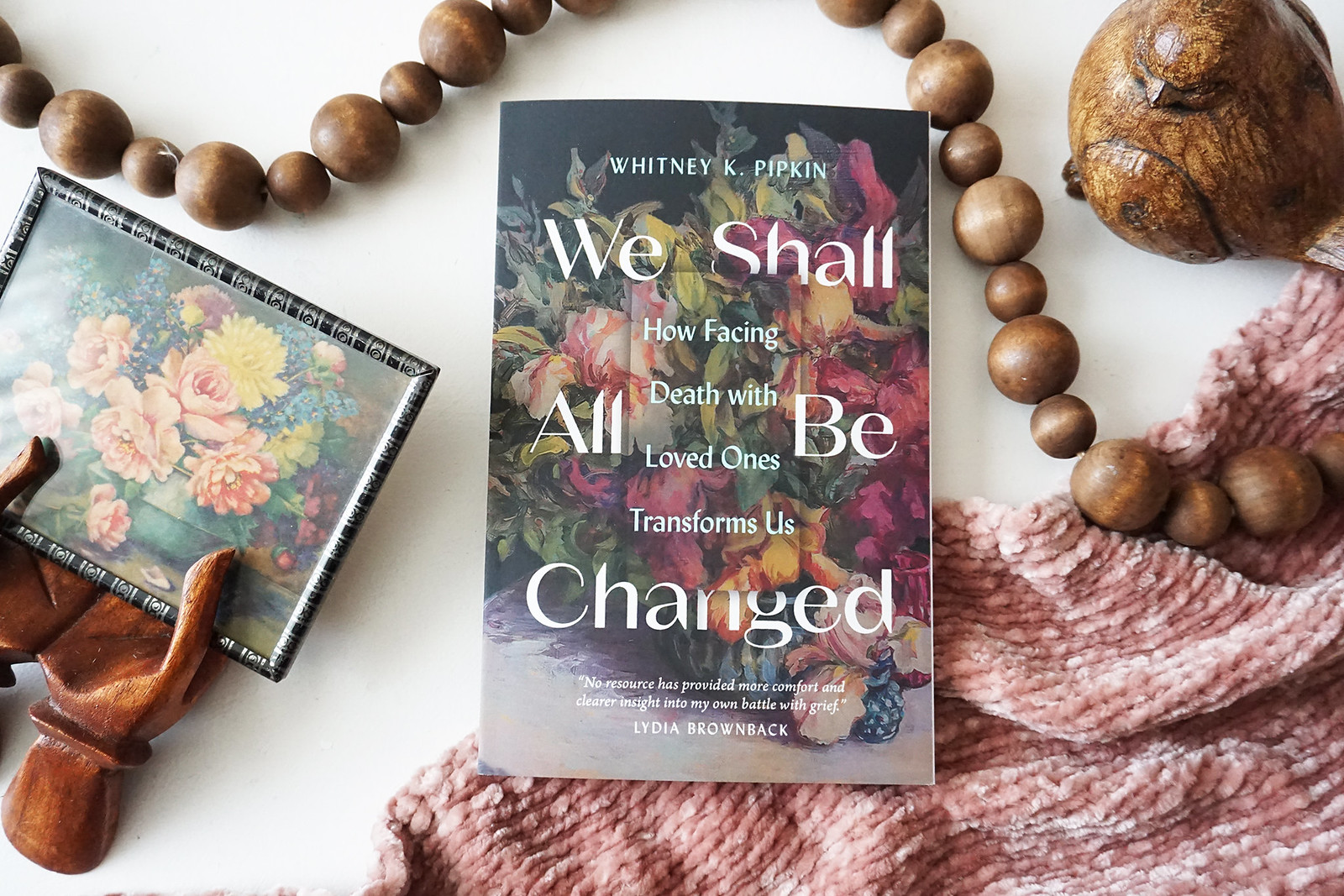

After losing her mom to the cancer she wrestled with for 20 years, Whitney has written We Shall All Be Changed: How Facing Death with Loved Ones Transforms Us a book she prays will serve others walking similar roads. You can find her on Instagram @whitneykpipkin and sign up for her newsletter at whitneykpipkin.com.

{Our humble thanks to Moody for their partnership in today’s devotional.}

*** “Body of death” (Rom. 7:24), “weak” (Matt. 26:41), “perishable” (1 Cor. 15:53). “For the creation was subjected to futility, not willingly, but because of him who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to corruption” (Rom. 8:20–21). See Genesis chapters 2 and 3. Quote from Genesis 3:19. “But when the fullness of time had come, God sent forth his Son, born of woman, born under the law, to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as sons” (Gal. 4:4–5). “Robed in frail humanity” phrase from Matt Papa, Matt Boswell, Michael Bleecker in the hymn, “Come Behold the Wondrous Mystery” (Love Your Enemies Publishing, 2013).