When Shawn Smucker agreed to meet a Syrian refugee named Mohammed at his local refugee agency in order to write and share his story, neither of them knew they had arrived in each other’s lives just in time. Neither knew the conversations they would have, the ways their families would come together, that this stranger would become a true friend. For all of us wondering how to respond to the refugee crisis we see on the news and in our own backyards, Shawn shares his deeply personal story—and Mohammad’s—to help us consider what it means to truly love our neighbors across cultural, political, and even religious divides. It’s an honor to welcome Shawn to tell his story on the farm’s front porch today…

The stories of other people are always hidden from us at first, waiting in the shadows.

They are tentative, skittish things, these hidden tales, frightened of what might become of them if they step out into the light.

When I first met Mohammad, there were things I never could have guessed about him, things I never could have imagined.

The man rides his motorcycle through the Syrian countryside, his wife and four sons somehow balanced on the bike with him. He has received a tip that his village will soon be bombed. Their combined weight wobbles the motorcycle from side to side, and he shouts at them to hold still, hold still.

The man sits quietly on a friend’s porch, drinking very dark coffee, watching bombs rain down on his village miles away. “That was your house,” he says, then, ten minutes later, “I think that one hit my house.” He takes another sip of coffee. His children play in the yard.

The man walks through the pitch-black Syrian wilderness, his family in a line behind him. He can feel the tension in his wife, the fear in his older boys. Someone ahead shouts, “Get down!” and they all collapse into the dust, holding their breath, trying to keep the baby quiet. There is the taste of dirt. There are rocks digging into his body. There is the sound of his boys, afraid, so far from home.

“Abba,” they whimper. “Abba.”

There are nearly 6,000 miles between Mohammad’s hometown and Lancaster, Pennsylvania. There are dozens of other countries he could have been relocated to. Hundreds of other cities.

Yet somehow he came here, less than a mile from my house, to the area where my ancestors have lived for the last 250 years.

What are the odds of these crossings?

*****

I thank Mohammad through a translator for his willingness to meet me here in a strange country even when he does not know what telling his story might lead to.

“It may very well be that nothing will come of our time together,” I say. “But I would like to help you tell your story.”

The translator echoes my words to Mohammad in his own language, and he smiles and nods and answers in Arabic. My translator smiles and nods again, and turns to me.

“Mohammad says it is impossible for nothing to come of this. He is glad you are willing to hear his story, and no matter what happens, you are friends now. That is all that matters.”

The words catch me off guard. I pause, aware of my own breathing.

I thought this Middle Eastern man would be more skeptical about me. I thought he, a Middle Eastern Muslim, would see me, a white, western, Christian man, as a potential enemy. But he accepts me without reservation, almost instantly. His quick willingness to befriend me puts me off balance.

Friend. I wonder what he thinks when he says that word, and perhaps for the first time ever, I wonder what the word means to me.

Am I a good friend? My life is fairly isolated, dedicated mostly to my wife and children.

Do I know what the word friend means?I clear my throat, try to think of questions to ask. “Mohammad, can you tell me about your village?” I ask him. “Can you tell me about how you got to the United States?”

Bilal relays the question, and Mohammad looks up at me. He smiles a sad smile.

“I love Syria. No one ever wants to leave their home. But we had no choice.”

*****

When I set out to write Mohammad’s story a year ago, I thought it would perhaps be an action-adventure tale following a Syrian family through bombs and bullets to an inner-city US neighborhood that persecuted them for being Muslim. I thought it might be the tale of how a middle-aged man in search of meaning helped a Syrian family find the American dream.

Instead, something happened inside of me.

My belief that refugees have little to offer was crushed.

My belief that they need my help more than they need my friendship was brought low.

My deep-seated, hidden concern that every Muslim person might be inherently violent or dedicated to the destruction of the West was exposed and found to be false.

The story I planned to write and the story I have actually written are as dissimilar as the relationship I thought I would have with Mohammad and the one I actually have.

When I decided to reach out to Mohammad, when I decided to “help,” I envisioned taking his family food or finding them furniture they needed or emailing him the address of the DMV.

The help I was prepared to offer was help given at arm’s length, aid that would cost me perhaps a tiny bit of time and maybe a few dollars but not much more than that.

But I, not Mohammad, needed more than that. Actually, it turns out we both needed the same thing. We both needed a friend.*****

Who is my neighbor?

Friendship is such a strange, unexpected thing. It can creep up on you when you least expect it, from the least likely places. I never could have imagined I’d become friends with a Syrian man from 6,000 miles away, a Muslim man whose children call him Abba.

In the last year, Mohammad has changed my life in ways difficult to explain or describe. The coffee, the drives to Philadelphia, the chats on my front porch.

There’s one thing I know for sure.

If you insert me into the story of the good Samaritan, I’m not only the good Samaritan; I’m not only the one who stopped to help.

I’m also the man lying along the side of the road, beaten down.

I’m the one dying from selfishness and hypervigilance and fear.

The role of the good Samaritan, in a role reversal I couldn’t have seen coming, has been taken on by Mohammad.

Before I even knew him, he called me friend.

Shawn Smucker is the author of the novels The Day the Angels Fell and The Edge of Over There. He lives with his wife and six children in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

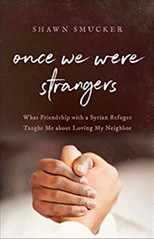

Shawn’s new memoir Once We Were Strangers: What Friendship with a Syrian Refugee Taught Me about Loving My Neighbor is a deeply personal story of two fathers hoping for the best, two hearts seeking compassion, two lives changed forever. It’s the story of our moment in history—and the opportunities it gives us to show love and hospitality to the sojourner in our midst.

Read this book and let your own eyes and heart be opened wider.

[ Our humble thanks to Baker for their partnership in today’s devotion ]