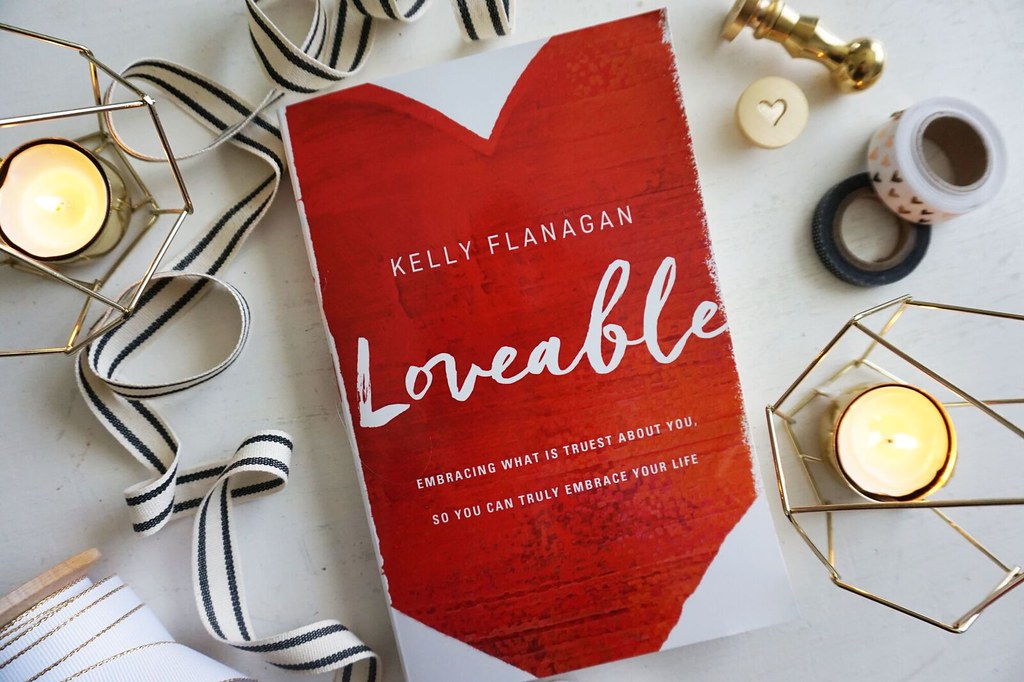

In 2014, clinical psychologist Kelly Flanagan and his daughter Caitlin wound up on the TODAY Show, after his letter about her inner and outer beauty, which he had published on his blog went viral. Following their television appearance, Kelly realized people were not sharing his words primarily because they were parents of little ones, but because each of us still has a little one inside of us, who is desperate to be reminded of three things: we are worthy, we are not alone, and we matter. That insight evolved into his new book, Loveable, a portion of which you will read here today. Kelly has an uncanny ability to weave the Good News into his writing in ways that are attractive and inviting to all people. His words are rooted in the knowledge of God’s grace and his belief that we can all participate in God’s redemptive story by embracing that we are loveable, living beloved, and doing what we love with our one precious life. It’s a grace to welcome Kelly to the farm’s front porch today…

I was born to a drug dealer and his quiet wife.

When I was two, he was caught in the act and incarcerated, and by the time I saw him again, he had become a Christian.

I was too young to remember any of it, but a lot changed after that. That’s when we started going to church on the weekends and, a little later, my parents started going to college during the week.

Two tuition payments plus three children equaled eight years of scarcity.

By the time I was in third grade, we were scraping by in a mobile home, with my mother working as a nurse at night and my father going to school during the day. What they did was heroic.

Sometimes, heroism isn’t very glamorous.

We had a television that broadcast mostly static, a car that couldn’t make right turns, and the constant trailer park fear of tornadoes.

We had fights about grocery money. We had fights about every kind of money.

We had a claustrophobic hallway that ended at a claustrophobic bedroom I shared with my brother. We had a basketball hoop down the street—an old rusted rim tied to a telephone pole with yellow twine. No backboard. No net. We had bullies who chased me home from the basketball court.

I usually got away.

We had a tiny bathroom in our trailer with a tiny bathtub. Sometimes we had hot water. Sometimes we didn’t.

One night, when we didn’t, my dad had a little anger. My mom was at work, and he said he was leaving too. He tried, but I wrapped myself around his leg and wouldn’t let go. He stayed.

But my shame stayed too.

I had a friend who didn’t live in the trailer park.

His dad was a doctor, and their car could turn in both directions. His TV had options, and his house was attached to the ground. His basketball hoop had a garage behind it, and his bathtub had water at whatever temperature you wanted.

He had boxes full of G.I. Joe action figures, and we played with them on a lawn made of grass instead of dust. His yard had a fence that kept the bullies out. And his parents didn’t look like they were on the verge of leaving anytime soon. They were affluent and they seemed happy, and when I was with them, for some reason, I felt a little less alone, a little less ashamed.

So, at some point, I decided making money could make me worthy.

Shame comes and goes and it’s hard to put a finger on the exact moment of its birth.

But once it is born, it almost always grows into the same conclusion: I’m not filled with worthiness, so I will try to surround myself with it.

I may not be a valuable thing, but I can purchase valuable things.

When you doubt the quality of your heart, you increase the quantity of your stuff.

You tell yourself the next gadget will make everything better. Or the next house. Or the next investment.

And before long, you’ve confused your net worth with the worth of your soul.

On an afternoon almost three decades after moving out of the mobile home, I’m digging through old boxes for a book called Rascal—a book given to me on the eve of moving away, as a farewell gift from the parents of my friend with the fence and the lawn made of grass instead of dust.

The corners are frayed and the pages are brittle, but when I lift the front cover, I see faded blue ink on the first blank, yellowing page. In script clearly written with great care, my friend’s mother had written these words: “To Kelly, who is anything but a rascal . . . May you grow in the grace and knowledge of the Lord.” It was signed and dated May 1986.

I was nine.

For thirty years, I had attributed my warm memories of their family to the stuff they had, and then chased after the same kind of stuff for myself.

On this afternoon, though, I realize I’ve gotten it all wrong.

I don’t remember them warmly because of their good stuff; I remember them warmly because of the good stuff they saw in me.

I remember them warmly because they gave me—the poor kid from the other side of the tracks—a chance to see my true self reflected in their eyes.

I remember them because the little one who clung to his father’s leg, terrified of being abandoned, needed desperately to be assured he wasn’t a rascal—he needed to know he was loveable.

I remember them because they were grace to me.

Years ago, these good people wrote these good words about me and for me, and the words sat neglected and mostly forgotten in a box all that time.

I think that’s how our hearts work too.

People write good things on them, but until we’re ready to read and receive the grace they are trying to speak into us, we close up our heart like a book and pack it away.

Instead of opening up the front cover of who we are to find the little bit of love that has been inscribed on us, we open up our wallets and try to find worthiness another way.

Perhaps it’s time we put away our wallets and dig our hearts out of the box.

Perhaps it’s time to open them up and read the good words people have written there.

Perhaps it’s time we dare to believe that the people who have loved us well—even if briefly and fleetingly—have seen us more accurately than we’ve seen ourselves.

Perhaps then we’d know:

Life isn’t about getting rich; it’s about living richly.

Kelly Flanagan is a licensed clinical psychologist, husband, and father of three. On his blog at drkellyflanagan.com he writes weekly about how to live redemptive stories right now.The story he shares today is from his newly released book Loveable: Embracing What Is Truest About You, So You Can Truly Embrace Your Life. In Loveable, Kelly reveals the core insight gleaned from his years of clinical work: you are here for a reason, yet you cannot truly awaken to it until you have first embraced your truest, worthiest self and then allowed yourself to be truly embraced by others.

Weaving together heart-warming storytelling, gentle insights, and the wisdom of his Christian faith—including Kelly’s belief that we are all “the living, breathing bearers of the eternal, transcendent, and limitless Love that spun the planets and hung the stars”—these pages will invite you to remember the name you were given before all other names: Loveable.

[ Our humble thanks to Zondervan for their partnership in today’s devotion ]