She would probably prefer it if you did not know her name, and yet her courageous decision to go public with her allegations of abuse against former USA Gymnastics team doctor Larry Nassar emboldened more than 250 other young women and girls to speak out, sending Nassar to prison for life and shining a long-overdue spotlight on decades of abuse and corruption within USA Gymnastics. A fierce victim’s advocate, Rachael Denhollander has become a defining voice, helping people recognize and understand the dynamics of abuse and empowering others to protect the most vulnerable in our families, churches, and communities. It’s a grace to welcome Rachael to the farm’s front porch today…

guest post by Rachael Denhollander

Much of what I know about love and forgiveness, I learned from my parents.

They taught us that love was the foundation for everything.

Love, they said, didn’t thrive on authority; it thrived on sacrifice.

Love sought to communicate and understand.

Love was humble, admitting wrongs and seeking to repair the damage.

Love protected.

And of course, behind everything was love for Jesus Christ.

My parents had an uncanny ability to weave truths from the Bible into almost every situation. In fact, I came to understand my own sin and need for forgiveness through a most unusual vehicle—toilet paper.

I was the ripe old age of three and fascinated with the cardboard roll that the toilet paper was wound around.

There were so many imaginative possibilities when one possessed a few of those tubes. Then one fateful day, there was no empty toilet paper roll to be found, and I had to have one for the current adventure I’d concocted.

So I slipped into the bathroom—quietly, for I knew what I was about to do was strictly forbidden—and tiptoed up to the full toilet paper roll. With the door closed, I furtively began unwinding the toilet paper so I could get at that magic tube underneath.

Significantly into my endeavor, I realized I was leaving a rather obvious trail of my illegal activities strewn all over the floor. Undaunted, I began stuffing all the emptied toilet paper straight into the toilet—and that is where my mother found me—hurriedly shoving paper into the toilet.

My mother calmly asked me what I’d done. I knew the word for it—sin. I’d chosen to rebel against what I’d been told.

Then my mom connected the dots for me. I wasn’t the only one who had disobeyed; Adam and Eve had too. Just as they had tried to hide their sin unsuccessfully, my efforts to hide my sin had been futile, and no amount of good things I might otherwise do would undo the sin already committed.

Even at my young age, I realized how desperately I needed a Savior.

Right then and there, I repented of my sin, turned to Christ for forgiveness and salvation, and in doing so, became a pastor’s worst nightmare—a stubborn three-year-old insistent upon being baptized.

I’d been forgiven of my sins, and I knew I was supposed to publicly declare it. So that Sunday, I rushed up to our pastor and explained what had happened and what I was ready to do. Somehow, however, the issue seemed less clear-cut to him. He hemmed and hawed, and told my parents he didn’t baptize children until they were at least eight. I was devastated. And I was frustrated.

“He is keeping me from obeying Jesus!” I protested.

I appealed to him again the following Sunday. And the next. And the next. He remained resolute.

Finally, my dad realized I wouldn’t be able to rest until I had done what I knew I was supposed to do.

So on a hot summer’s day, he pulled our little blue wading pool into the middle of the backyard, tucked the green garden hose into it, and filled it. I remember climbing into the cold water and kneeling down.

I gave my testimony and recited my favorite Bible verse, then I covered my mouth and nose with my hands, and my dad baptized me. I still remember the relief and joy that washed over my soul as tangibly as the cold water swept over my skin. I had been obedient.

When I eventually reached the magic age that my pastor had designated for “real” baptism, I joyfully participated, knowing full well it was only a continuation of what I’d already expressed and begun many years before.

My parents were also quick to ask forgiveness when they had been wrong. Taking responsibility for the choices we each made, being humble enough to admit those choices, and asking forgiveness was nonnegotiablein our family.

I appreciated this, because I’d seen what it looked like when that didn’t happen.

When I was little, I watched a family we were close to fall apart as the result of abuse.

The dad had massive anger issues, and when something didn’t go his way, he exploded on his gentle wife and young children.

He always had reasons—they had done something to cause it, he’d say. And he’d often acknowledge that he should have responded differently, but his apologies were always followed with a “but you . . .”

The day everything came to a head was my first experience holding a weeping abuse victim. She was in her thirties; I was nine.

I will never forget standing on my tiptoes, reaching up to hold her while she wept, and wanting to throw up because my grief at the damage that had been done to her made me physically ill. Later, my parents talked with us kids about what we had seen.

“This is what abusers do,” they explained. “Everything centers on them. Even when they apologize, they keep the focus on themselves—how they’ve been wronged or what they think they’ve done well—to try to shift the focus away from the pain they’ve caused. They don’t truly take responsibility for anything.”

Abusers pass the blame to others, they told me.

But that’s not what love does.

Love cares first about the harm done to the other person.

Unlike abuse, love does not excuse or minimize wrongdoing.

“When you’ve hurt someone,” my parents said, “and need to apologize, you say, ‘I’m sorry for blank,’ and then you stop. You don’t say anything else to justify, minimize, or excuse what you’ve done. You are always responsible for your choices, no matter what someone else did.”

The pattern of sacrificial love that was displayed by Christ on the cross was the one my parents followed and modeled for me daily, and it is what my husband and I strive to model for our own children.

My parents taught me that the greatest struggles, and most important choices, would come in the little things.

Where it felt easy to excuse an unloving response, and difficult to choose faithful love.

And yet it is these battles, these daily small choices, that shape who we really are and set the trajectory for our life.

I find I often learn best through stories, so the book Hinds’ Feet on High Places became for me a beautiful expression of this truth.

One of my favorite scenes remains when the Shepherd brings Much-Afraid up the mountain, to a field full of flowers, and Much-Afraid wonders aloud why such beauty would be put where no one can see it.

With gentleness, the Shepherd looks down and reminds her,

“Nothing my Father and I have made is ever wasted. . . . I must tell you a great truth, Much-Afraid, which only the few understand. All the fairest beauties in the human soul, its greatest victories, and its most splendid achievements are always those which no one else knows anything about, or can only dimly guess at. Every inner response of the human heart to Love and every conquest over self-love is a new flower on the tree of Love.”

Let us cultivate these flowers every day, in the greatest, and smallest, of ways.

Rachael Denhollander is an attorney, advocate, and educator who was the first woman to speak out publicly against USA Gymnastics team doctor Larry Nassar, one of the most prolific sexual abusers in recorded history. As a result of her activism, more than 250 women came forward as survivors of Nassar’s abuse, leading to his life imprisonment. Rachael and her husband, Jacob, live in Kentucky with their four children.

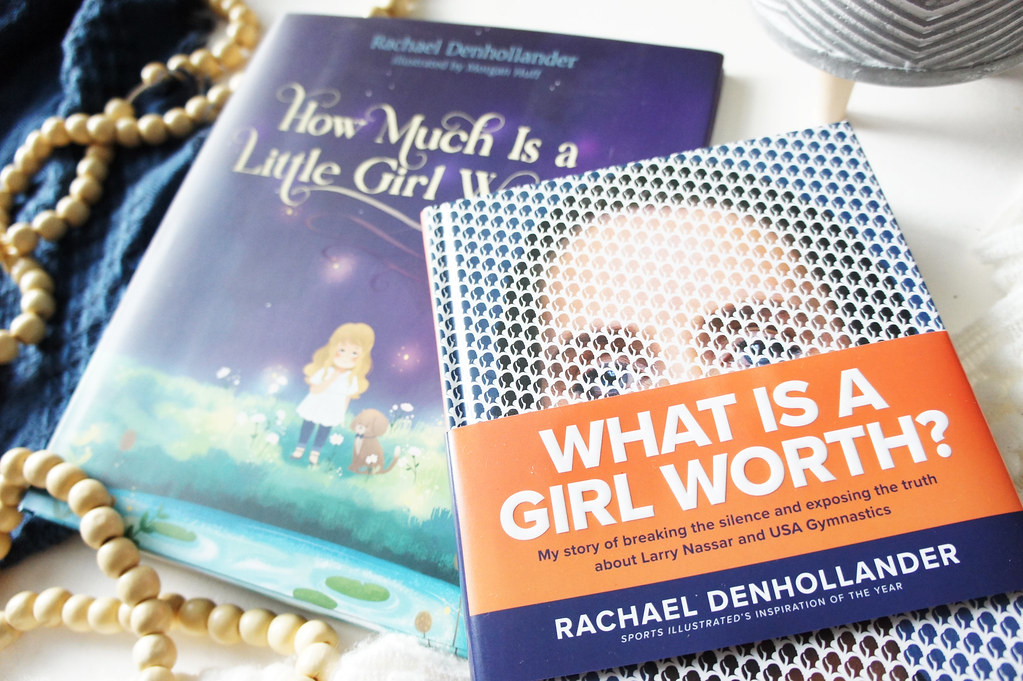

Her memoir, What Is a Girl Worth? is the inspiring true story of Rachael’s journey from an idealistic young gymnast to a strong and determined woman who found the courage to raise her voice against evil, even when she thought the world might not listen.

And her newly released children’s book, How Much Is a Little Girl Worth? is Rachael’s tender-hearted anthem to little girls everywhere, teaching them that they have immeasurable worth because they are made in the image of God.

[ Our humble thanks to Tyndale for their partnership in today’s devotion ]