Terri Kraus first experienced the Les Misérables musical at the historic Auditorium Theater in Chicago in the spring of 1989. Thus began her deep love and appreciation of the Christian themes of this unforgettable story. In this abridgment she have sought to capture the essence of the story, the human drama, the power of grace, and the rich spiritual awakening of the characters while maintaining the integrity of Hugo’s original work. What an amazing honor and privilege it’s been for her to be entrusted with the abridgment of this epic novel for this exquisitely illustrated version. I hope it will cause you, too, to love this captivating, compelling, and inspiring story! It’s a grace to welcome Terri and the works of Victor Hugo to the farm’s front porch today…

guest post by Victor Hugo and Terri Kraus

N

ot a door in the bishop’s house was locked. Formerly loaded with bars and bolts like the door of a prison, the bishop had all this removed. They were easily opened with a simple push.

The bishop had written three lines in the margin of a Bible: “The door of a physician should never be closed; the door of a priest should always be open.”

That evening, there was a loud knock on the door of the bishop of Digne.

A traveler entered, with a rough, hard, tired, and fierce look in his eyes. He was hideous.

The man said loudly, “My name is Jean Valjean. I am a convict, nineteen years in the galleys, four days ago set free. I have walked twelve leagues. I went to an inn, and to the prison. Nobody here would have me. A good woman showed me your house, and said, ‘Knock there!’ What is this place? I have money, which I have earned in the galleys. I am very tired—and I am so hungry. Can I stay?”

“Madame Magloire,” said the bishop to his housekeeper, “put on another plate.”

“Stop!” the traveler exclaimed. “Did you understand me? I am a galley-slave, a convict.”

He drew from his pocket a sheet of yellow paper. “My passport. It says, ‘Jean Valjean, a liberated convict—five years for burglary; fourteen years for attempted escape four times. Very dangerous.’ Everybody has thrust me out. Have you a stable?”

“Madame Magloire,” said the bishop, “put some sheets on the bed in the alcove. Monsieur, sit down and warm yourself. We will take supper.”

At last the man understood; his face, which had been gloomy and hard, now expressed stupefaction, doubt, and joy, and became absolutely wonderful.

“What! You won’t drive me away? You call me monsieur and don’t say, ‘Get out, dog!’ I shall have supper, and a bed like other people with mattress and sheets? You are a fine man, an innkeeper, aren’t you?”

“I am a priest who lives here.”

“A priest! You are the curé of this big church? How stupid I am; I didn’t notice your cap. You are humane, Monsieur Curé. Then you don’t want me to pay you?”

“No,” said the bishop, “keep your money.”

“Monsieur Curé, you don’t despise me. You take me in and I haven’t kept from you where I come from and how miserable I am.”

The bishop touched his hand and said,

“You need not tell me who you are. This is not my house; it is the house of Christ. It does not ask any comer whether he has a name, but whether he has an affliction. You are suffering; you are hungry and thirsty; be welcome.

And do not thank me. This is the home of no man, except him who needs an asylum. I tell you, who are a traveler, that you are more at home here than I; whatever is here is yours. What need have I to know your name?

Besides, before you told me, I knew it.”

The man, astonished, said, “Really? You knew my name?”

“Yes,” answered the bishop, “your name is My Brother.”

Meantime Madame Magloire had served up supper. The man fell to eating greedily. The bishop said grace, and said to the man, “I will show you to your room.” Then he led his guest into the alcove, before a clean white bed.

The traveler asked, “Who tells you that I am not a murderer?”

The bishop responded, “God will take care of that.”

Then, moving his lips like one praying, he raised two fingers of his right hand and blessed the man, who, however, did not bow, and went into his chamber.

*******************

Les Misérables is inspired by the June Rebellion in Paris. In 1832, a throng of tens of thousands stormed the Bastille, infuriated by economic hardships, food shortages, and the callous attitudes of the upper classes.

It depicts the misery of the impoverished Parisian underclass who had little voice in society. Hugo provides that voice. The June Rebellion was largely forgotten until 1980, when the astoundingly popular musical version of Les Misérables opened on a London stage.

The book begins in 1815 and tells the fictional story of Jean Valjean, unjustly condemned to nearly two decades of prison for stealing a loaf of bread to save his widowed sister’s starving children.

Upon his release, treated like an outcast everywhere, he loses all hope, until the good Bishop Myriel takes him in and blesses him with God’s love, causing him to create a new life for himself.

The bishop’s compassion, pointing him to Christ, is the spark that begins the dramatic transformation in Valjean’s life.

But for decades he is hunted by the ruthless policeman Inspector Javert, who is obsessively devoted to enforcing the letter of the law. Valjean, miraculously saved for God’s work, chooses to care for Fantine—a desperate, dying factory worker who has been forced into prostitution—and later her orphaned daughter, Cosette. These decisions change their lives forever.

Les Misérables is a moving story of the power of grace redirecting one’s life, and how striving for salvation through works can be destructive.

In the original text, Hugo uses the word transfiguration—a complete change of form or appearance into a more beautiful or spiritual state—to describe the total transformation of Valjean through the power of the gospel.

Today’s world is full of the same injustice, depravity, conflict, suffering, and hopelessness as the world was in 1815—evidenced by the disturbing events we read about in the news. And yet, the gospel is still just as powerful to transfigure the lives of sinners.

The questions I ask myself are,

“Am I that spark? Do I, like Bishop Myriel, respond to people as those created in the image of God—with a warm, compassionate heart? Am I an open door? Do I call them ‘brother’ or ‘sister’?

Or am I more like Inspector Javert, whose legalism became the driving force behind his actions? When choosing to either condemn or forgive, am I filled with the astonishing grace that Jesus, the sinless Son of God, showed even the worst of sinners?”

These questions have driven me to my knees, asking Christ to humble and fill me with the unconditional love that sent Him to the cross to die for the sins of mankind.

They require me to let go of my self-righteousness and acknowledge my own sinfulness.

This Bishop Myriel kind of compassion could be transformational because it is the same kind of unfathomable love that God offered undeserving me.

It has the potential to cause sinners to turn from sin, and to be the spark that begins the transformation of their lives.

Terri Kraus is the author of three novels—the Project Restoration series—and one upcoming devotional, Farmhouse Retreat. She is also the coauthor of ten novels with her husband, award-winning, bestselling author Jim Kraus.

Victor Hugo (1802-1885) was a French novelist of the Romantic movement. He was a reformer whose aim was twofold: in literature, he fought for truth; in politics, for the cause of the people. He wrote many volumes of poetry, but he is best known outside of France for his novels Les Misérables and The Hunchback of Notre-Dame. He was a great campaigner for social causes, especially the poor. He published Les Misérables, a major novel about social misery and injustice, in 1862. Hugo died at the age of eighty-three.

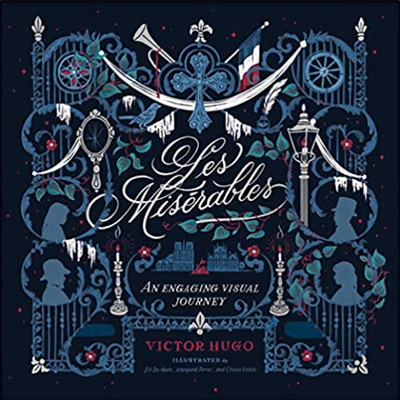

Les Misérables is a story of compassion, forgiveness, justice, and the will to survive amid the shadow of turmoil and revolution. For the first time, Victor Hugo’s masterpiece is a mixed-media special edition complete with French-inspired watercolor paintings, decorative hand-lettering, vintage imagery, and space for journaling and reflection. As you read and connect with this unique, artfully-designed Visual Journey, its pages become a canvas on which to chronicle your own story, struggles, and personal triumphs.

Since its first publication in 1862, Les Misérables has inspired millions of people to embrace sacrificial agape love and kindness, and to extend care and compassion to the poor and marginalized.

[ Our humble thanks to Tyndale for their partnership in today’s devotion ]